The Love of César Moro

Beatriz Hausner

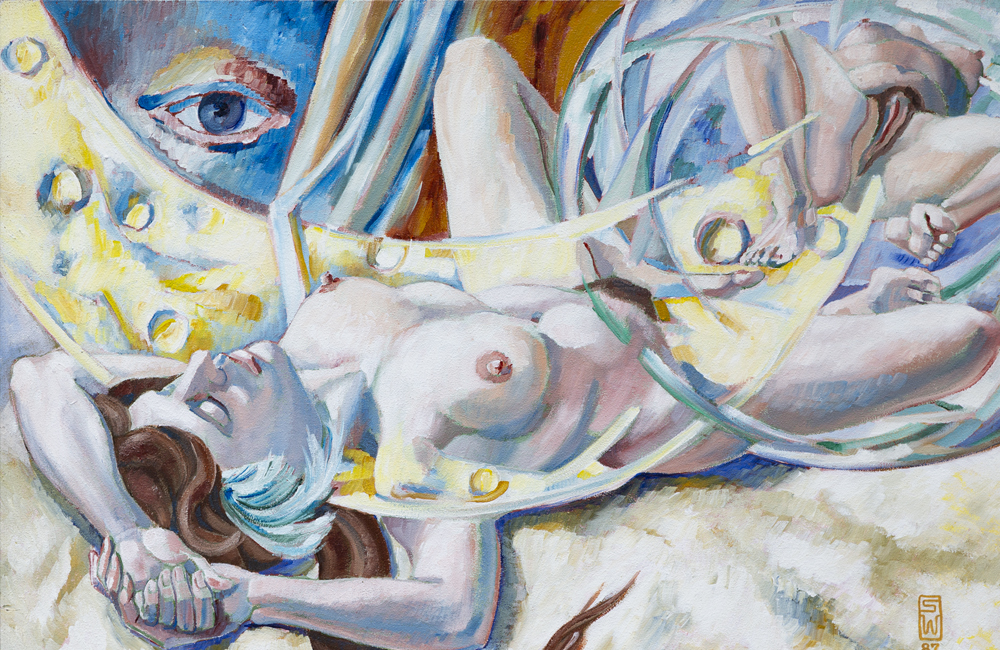

From the outset, when delving into translating César Moro’s poetry, a strange siblinghood established itself, stirring the poet in me. Translating, transferring poetics from one language to another does teach one. Translation is, without question, the deepest reading. With Moro, however, something else was at work: his imagery, the sheer force of his expression of Eros, caused the pieces of the puzzle that was my poetics to change in ways I could not have envisioned during those early attempts at translating his work. As I progressed, I experienced a marvelling at his expression of the beloved’s ecstasy ¾ his for his guys, mine for mine ¾, an intensity taken to the point of annihilation of the self through love for the Other.

The revelation came while translating César Moro’s “Carta de amor,” which I had first read in a Spanish translation by Ricardo Silva-Santisteban in La tortuga ecuestre y otros textos, a selection of his poetry published by Monte Avila Editores (Caracas, 1976). That book came into our home soon after its publication. I assume that Ludwig Zeller, my late stepfather bought it at Macondo Books, a bookstore my parents would visit during their periodic pilgrimages to New York City in search of literary resources entirely lacking in Toronto at the time. In fact, it was through Ludwig that I first heard of “Carta de amor.”

“Lettre d’amour” was created in Mexico, during a period of César Moro’s life that would prove transformative and extremely fruitful. The manuscript of the poem, written in long hand by Moro, and dated 1942, was first published in 1944 in Mexico City by Éditions Dyn, Wolfgang Paalen’s extraordinary publishing imprint, in a limited edition of 50 copies, with an original etching signed by Alice Paalen (née Rahon).

The first Spanish translation was by Moro’s lifelong friend, the Peruvian poet Emilio Adolfo Westphalen, who published it in his Las moradas (eight issues, between 1947 and 1948), an immensely influential literary magazine, which would provide access, in Spanish translation, to the newest literary values of international literature to a new generation of Latin American creators. Moro became an assiduous contributor to Las moradas, with articles as wide ranging as his take on the effects of dream in Marcel Proust’s “El sueño de la cena de Guermantes” (his translation), his impressions of Mexico City, translations of French poets like Pierre Reverdy and his surrealist colleagues (including a two-part translation of Leonora Carrington’s Down Under, which she’d just written), as well as book reviews.

Here is the original text:

Lettre d’amour

Je pense aux holothuries angoissantes qui souvent nous entouraient à l’approche de l’aube

quand tes pieds plus chauds que des nids

flambaient dans la nuit

d’une lumière bleue et pailletée

Je pense à ton corps faisant du lit le ciel et les montagnes suprêmes

de la seule réalité

avec ses vallons et ses ombres

avec l’humidité et les marbres et l’eau noire reflétant toutes les étoiles

dans chaque œil

Ton sourire n’était-il pas le bois retentissant de mon enfance

n’étais-tu pas la source

la pierre pour des siècles choisie pour appuyer ma tête ?

Je pense ton visage

immobile braise d’où partent la voie lactée

et ce chagrin immense qui me rend plus fou qu’un lustre de toute beauté balancé dans la mer

Intraitable à ton souvenir la voix humaine m’est odieuse

toujours la rumeur végétale de tes mots m’isole dans la nuit totale

où tu brilles d’une noirceur plus noire que la nuit

Toute idée de noir est faible pour exprimer le long ululement du noir sur noir éclatant ardemment

Je n’oublierai pas

Mais qui parle d’oubli

dans la prison où ton absence me laisse

dans la solitude où ce poème m’abandonne

dans l’exil où chaque heure me trouve

Je ne me réveillerai plus

Je ne résisterai plus à l’assaut des grandes vagues

venant du paysage heureux que tu habites

Resté dehors sous le froid nocturne je me promène

sur cette planche haut placée d’où l’on tombe net

Raidi sous l’effroi de rêves successifs et agité dans le vent

d’années de songe

averti de ce qui finit par se trouver mort

au seuil des châteaux désertés

au lieu et à l’heure dits mais introuvables

aux plaines fertiles du paroxysme

et de l’unique but

ce nom naguère adoré

je mets toute mon adresse à l’épeler

suivant ses transformations hallucinatoires

Tantôt une épée traverse de part en part un fauve

ou bien une colombe ensanglantée tombe à mes pieds

devenus rocher de corail support d’épaves

d’oiseaux carnivores

Un cri répété dans chaque théâtre vide à l’heure du spectacle inénarrable

Un fil d’eau dansant devant le rideau de velours rouge

aux flammes de la rampe

Disparus les bancs du parterre

j’amasse des trésors de bois mort et de feuilles vivaces en argent corrosif

On ne se contente plus d’applaudir on hurle

mille familles momifiées rendant ignoble le passage d’un écureuil

Cher décor où je voyais s’équilibrer une pluie fine se dirigeant rapide sur l’hermine

d’une pelisse abandonnée dans la chaleur d’un feu d’aube

voulant adresser ses doléances au roi

ainsi moi j’ouvre toute grande la fenêtre sur les nuages vides

réclamant aux ténèbres d’inonder ma face

d’en effacer l’encre indélébile

l’horreur du songe

à travers les cours abandonnées aux pâles végétations maniaques

Vainement je demande au feu la soif

vainement je blesse les murailles

au loin tombent les rideaux précaires de l’oubli

à bout de forces

devant le paysage tordu dans la tempête

México, D.F., décembre 1942

Here is Emilio Adolfo Westphalen’s Spanish translation of “Lettre d’amour,” published in issue 5 of Las moradas (1948):

Carta de amor

Pienso en las holoturias angustiosas que a menudo nos rodeaban al acercarse el alba

cuando tus pies más cálidos que nidos

ardían en la noche

con una luz azul centelleante.

Pienso en tu cuerpo que hacía del lecho el cielo y las montañas supremas

de la única realidad

con sus valles y sus sombras

con la humedad y los mármoles y el agua negra reflejando todas las estrellas

en cada ojo.

¿No era tu sonrisa el bosque resonante de mi infancia

no eras tu el manantial

la piedra desde siglos escogida para reclinar mi cabeza?

Pienso tu rostro

inmóvil brasa de donde parten la vía láctea

y ese pesar inmenso que me vuelve más loco que una araña encendida agitada sobre el mar.

Intratable cuando te recuerdo la voz humana me es odiosa

siempre el rumor vegetal de tus palabras me aísla en la noche total

donde brillas con negrura más negra que la noche.

Toda idea de lo negro es débil para expresar la larga ululación de negro sobre negro resplandeciendo ardientemente.

No olvidaré nunca

Pero quién habla de olvido

en la prisión en que tu ausencia me deja

en la soledad en que este poema me abandona

en el destierro en que cada hora me encuentra.

No despertaré más.

No resistiré ya el asalto de las grandes olas

que vienen del paisaje dichoso que tú habitas.

Afuera bajo el frío nocturno me paseo

sobre aquella tabla tan alto colocada y de donde se cae de golpe.

Yerto bajo el terror de sueños sucesivos agitados en el viento

de años de ensueño

advertido de lo que termina por encontrarse muerto

en el umbral de castillos desiertos

en el sitio y a la hora convenidos pero inhallables

en las llanuras fértiles del paroxismo

y del objetivo único

pongo toda mi destreza en deletrear aquel nombre adorado

siguiendo sus transformaciones alucinantes.

Ya una espada atraviesa de lado a lado una bestia

o bien una paloma cae ensangrentada a mis pies

convertidos en roca de coral soporte de despojos

de aves carnívoras.

Un grito repetido en cada teatro vacío a la hora del espectáculo

indescriptible.

Un hilo de agua danzando ante la cortina de terciopelo rojo

frente a las llamas de las candilejas.

Desaparecidos los bancos de la platea

acumulo tesoros de madera muerta y de hojas vivaces de plata corrosiva.

Ya no se contentan con aplaudir aullando

mil familias momificadas vuelven innoble el paso de una ardilla.

Decoración amado donde veía equilibrarse una lluvia fina en rápida carrera hacia el armiño

de una pelliza abandonada en el calor de un fuego de alba

que intentaba hacer llegar al rey sus quejas

así de par en par abro la ventana sobre las nubes vacías

reclamando a las tinieblas que inunden mi rostro

que borren la tinta indeleble

el horror del sueño

a través de patios abandonados a las pálidas vegetaciones maníacas.

En vano pido la sed al fuego

en vano hiero las murallas

a lo lejos caen los telones precarios del olvido

exhaustos

ante el paisaje que retuerce la tempestad.

Here is my translation of “Lettre d’amour / Carta de amor,” which I based on the French original and on Silva-Santisteban’s 1976 translation:

Love Letter

I think of the anguishing holothurians that often surrounded us at the nearing of dawn

when your feet warmer than nests

burned in the night

in a glowing blue light.

I think of your body making sky and supreme mountains from the bed

I think of the sole reality

with its valleys and shadows

moisture and marble and black water mirroring the stars

in each of your eyes.

Your smile, was it not the echoing forest of my childhood?

Where you not the source

the stone destined centuries ago for me to rest my head on?

I conceive of your face

motionless ember source of the milky way

and of this immense sorrow driving me madder than a burning chandelier swaying over the sea

Unbearable when I think of you the human voice feels intolerable to me

always the vegetal murmur of your words isolates me in total darkness

where you shine with a blackness blacker than the night.

All idea of black is insufficient to express the long hooting of black on black glowing fervently.

I will not forget.

But who speaks of forgetting

in the prison where your absence leaves me

in the solitude this poems abandons me to

the exile each hour finds me in.

I will not wake up again

I will not resist the onslaught of great waves

that come from the joyful landscape you inhabit.

Outside in the cold of night I walk

the plank suspended above us and from where we fall flat.

Stiff with the fear of successive dreams and shaking in the wind

a single dream lasting years,

mindful of what may be found dead

at the threshold of deserted castles

at the place and time agreed upon but missed,

in the fertile plains of paroxysm

conscious of the single-most object,

I will use all my powers to spell

the name once adored

and will follow its hallucinatory transformations.

A sword is already piercing an animal

and a bleeding dove falls at my feet

becoming coral rock, buttress for the remains

of carnivorous birds.

A repeated scream in every empty theatre as the inconceivable performance is about to begin.

A rivulet of water dancing in front of the red velvet curtains

at the floodlights.

Once the orchestra seats have disappeared

I amass treasures of dead wood and hardy leaves of corrosive silver.

Not content with just clapping and shouting

a thousand mummified families make the passing of a squirrel seem evil.

Beloved decoration where I saw a fine rain balancing itself racing swiftly toward the ermine fur-lining

of a coat left behind in the heat of the fire at dawn

as it attempted to direct its grievances to the king.

I open the windows over the empty clouds

imploring darkness to drown my face

to erase this indelible ink

and the horror of dream

in courtyards abandoned to the pale manic vegetation.

In vain I implore fire to slake this thirst

in vain I wound the walls:

in the distance the precarious curtains of forgetting

fall, exhausted

before a landscape twisting in the storm.

Mexico, December 1942

The fact that César Moro wrote his most famous and emblematic Spanish poem in French proves that translation can effectuate enormous influence over a literary culture. The significance of this fact can’t be understated: roughly one half of Moro’s poetry is known and has come to influence successive generations of Latin American poets in Spanish translation1. “Lettre d’amour” exemplifies this phenomenon.

Born Alfredo Quíspez Asín in 1903 in Lima, Peru, Moro’s trajectory begins as a visual artist, with shows and publications of his art before he turned twenty. By then he had adopted the name César Moro. His earliest known poetry dates from that period. In 1925, in response to the oppressive conservatism of Peruvian society, Moro moved to Paris, where he would remain for the next decade. It was there that he became a French-language poet and became a member of the surrealist movement: he actively formed part of the Paris group’s activities, participated in their tracts and inquests, and published his poetry in their magazines. He returned to Lima in 1933, where he established a strong presence in the burgeoning literary and artistic scene. With the police after him, due to his political activities, in 1938 Moro moved to Mexico City, where he would come to write the largest part of his oeuvre in Spanish. Moro became a central figure of the literary and cultural renaissance that would see Mexico become home to artists, writers and publishers escaping the Spanish Civil war, as well as World War II. During this period of immense creative energy his work appeared in the major avant-garde publications of Mexico, including El hijo pródigo, where he published consequential articles. Notable among them is his response to Arcane 17, the book-length poem André Breton wrote during his sojourn in Québec (August to November of 1944). Arcane 17 was first published in New York by Brentano’s in early 1945, in a limited edition that included colour illustrations by Roberto Matta. Moro’s review of Breton’s famous work was mostly unfavourable: his criticism focused on Breton’s insistence on love of the Other as being strictly heterosexual. Moro frames his view by criticizing Breton’s failure to keep up with developments in psychology. When one considers that César Moro was writing ground breaking homoerotic poetry, while at the same time openly differing with his friend André Breton on the crucial issue of sexuality, one can’t but be astonished at his courage and honesty.

“Love Letter” signals a change in Moro’s poetics. There is flexibility, ease at expressing wildness and strangeness, combined with the stylistic elegance of the poetry he had been writing in French. It is as if his bilingualism, instead of constraining his expression, worked as a liberator of his voices, allowing him to invent an entirely new diction. What force, or event could have triggered Moro’s poetic liberation? More precisely, who could have inspired such an extraordinary love poem? It is a question that haunted me until I delved into the second important compilation of César Moro’s work, Obra poética (Lima: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, 1980), where I found six, until then unpublished texts, which function as letters to someone by the name of Antonio A.M., whom Moro had met in 1939, a year after his arrival in Mexico. Written originally in Spanish the letters contain many of the elements that Moro would incorporate into “Lettre d’amour.” The tonalities of the letters come through the French, only more densely so, rendered through Moro’s scintillating imagery, where elements contrary and often strange in the extreme come into juxtaposition with one another, in order to build a kind of cosmic landscape for the beloved.

Here is one of the letters in the original Spanish:

IV

Te quiero con tu gran crueldad, porque apareces en medio de mi sueño y me levantas y como un dios, como un auténtico dios, como el único y verdadero, con la injusticia de los dioses, todo negro dios nocturno, todo de obsidiana con tu cabeza de diamante, como un potro salvaje, con tus manos salvajes y tus pies de oro que sostienen tu cuerpo negro, me arrastras y me arrojas al mar de las torturas y de las suposiciones.

Nada existe fuera de ti, sólo el silencio y el espacio. Pero tu eres el espacio y la noche, el aire y el agua que bebo, el silencioso veneno y el volcán en cuyo abismo caí hace tiempo, hace siglos, desde antes de nacer para que de los cabellos me arrastres a mi muerte. Inútilmente me debato, inútilmente pregunto. Los dioses son mudos; como un muro que se aleja, así respondes a mis preguntas, a la sed quemante de mi vida.

¿Para qué resistir a tu poder? Para qué luchar con tu fuerza de rayo, contra tus brazos de torrente; si así ha de ser, si eres el punto, el polo que imanta mi vida.

Tu historia es la historia del hombre. El gran drama en que mi existencia es el zarzal ardiendo, el objeto de tu venganza cósmica, de tu rencor de acero. Todo sexo y todo fuego, así eres. Todo hielo y todo sombra, así eres. Hermoso demonio de la noche, tigre implacable de testículos de estrella, gran tigre negro de semen inagotable de nubes inundando el mundo.

Guárdame junto a ti, cerca de tu ombligo en que principia el aire; cerca de tus axilas donde se acaba el aire. Cerca de tus pies y cerca de tus manos, Guárdame junto a ti. Seré tu sombra y el agua de tu sed, con ojos; en tu seño seré aquel punto luminoso que se agranda y lo convierte todo en lumbre; en tu lecho al dormir oirás como un murmullo y un calor a tus pies se anudará [que] irá subiendo y lentamente se apoderará de tus miembros y un gran descanso tomará tu cuerpo y al extender tu mano sentirás un cuerpo extraño, helado: seré yo. Me llevas en tu sangre y en tu aliento, nada podrá borrarme. Es inútil tu fuerza para ahuyentarme, tu rabia es menos fuerte que mi amor; ya tu y yo unidos para siempre, a pesar tuyo, vamos juntos. En el placer que tomas lejos de mí hay un sollozo y tu nombre. Frente a tus ojos el fuego inextinguible.

18 de junio de 1939

Here is my translation:

IV

I love you with your great cruelty, because every time you appear in the middle of my dream you erect me, and like a god, like a veritable god, a true god, with the injustice of the gods, all black, you, my nocturnal god, made entirely of obsidian and with your diamond head, and like an untamed colt, with your wild hands and with your feet made of gold, which support your black body, you drag me and you hurl me into this sea of torment and of supposition.

Nothing but silence and space exists outside of you. And yet you are the space, the night, the air and the water I drink like a silent poison. You are the volcano into whose abyssal cavity I fell long since, perhaps centuries ago, before I was born, in order for you to drag me to my death. I question myself in vain, and in vain I ask, but the gods are silent. Like a wall moving away, you respond to my questions, to my life’s burning thirst.

Why resist your power? Why struggle against the lightning strength of your torrent arms? This is the way it must be, with you being the exact measure, the magnetic pole of my life.

Your story is the story of all people, the great drama wherein my existence is burning bramble, the object of your cosmic revenge, of your steely resentment. All sex and all fire, that is what you are. All ice and all shadow is how you must be. My beautiful night demon, implacable tiger with testicles made of stars, great black tiger of inexhaustible semen of clouds flooding the world.

Keep me close to you, next to your navel where the air begins, close to your armpits where the air ends, close to your feet and close to your hands. Keep me next to you.

I will be your shadow. I will be water to your thirst with these eyes. In your dream I will be the luminous spot that expands and turns everything into light. In your bed, while you sleep, you will hear murmuring: warmth will wrap itself around your feet as it rises and slowly takes over your extremities. A great calm will overwhelm your body and as you extend your hand, you will feel a strange and cold body next to yours: it will be me. You carry me in your blood and in your breath, and nothing will erase me. Your strength cannot banish me, your ire will always be less strong than my love. You and I forever joined, and despite you, we go on together. In the pleasure you take away from me there is weeping and there is your name. Before your eyes our inextinguishable fire.

June 18, 1939.

Another text corresponding to the same cycle of letters, closely modeled on the enumerative manner of André Breton’s legendary “L’union libre,” has Moro using his beloved’s name as the start of each line:

ANTONIO es Dios

ANTONIO es el Sol

ANTONIO puede destruir el mundo en un instante

ANTONIO hace caer la lluvia

ANTONIO puede hacer oscuro el día o luminosa la noche

ANTONIO es el origen de la Vía Láctea

ANTONIO tiene pies de constelaciones

ANTONIO tiene aliento de estrella fugaz y de noche oscura

ANTONIO es el nombre genérico de los cuerpos celestes

ANTONIO es una planta carnívora con ojos de diamante

ANTONIO puede crear continentes si escupe sobre el mar

ANTONIO hace dormir el mundo cuando cierra los ojos

ANTONIO es una montaña transparente

ANTONIO es la caída de las hojas y el nacimiento del día

ANTONIO es el nombre escrito con letras de fuego sobre todos los planetas ANTONIO es el Diluvio

ANTONIO es la época megalítica del Mundo

ANTONIO es el fuego interno de la Tierra

ANTONIO es el corazón del mineral desconocido

ANTONIO fecunda las estrellas

ANTONIO es el Faraón el Emperador el Inca

ANTONIO ANTONIO ANTONIO ANTONIO ANTONIO ANTONIO ANTONIO

nace de la noche

es venerado por los astros

es más bello que los colosos de Memnón en Tebas

es siete veces más grande que el Coloso de Rodas

ocupa toda la historia del mundo

sobrepasa en majestad el espectáculo grandioso del mar enfurecido es toda la Dinastía de los Ptolomeos

México crece alrededor de ANTONIO

Here is my translation:

ANTONIO is God

ANTONIO is the Sun

ANTONIO can destroy the world in an instant

ANTONIO is the rainmaker

ANTONIO makes turns day into dark and night into light

ANTONIO is the source of the Milky Way

ANTONIO’s feet are the constellations

ANTONIO’s breath is made of fleeting stars and of darkest night

ANTONIO is the generic name for all the celestial bodies

ANTONIO is a carnivorous plant with diamond eyes

ANTONIO conjures entire continents each time he spits at the sea

ANTONIO puts the world to sleep when he closes his eyes

ANTONIO is a transparent mountain

ANTONIO is the falling leaves and the birth of day

ANTONIO is the name written in fiery letters on every planet

ANTONIO is the Flood

ANTONIO is the megalithic age of the World

ANTONIO is the Earth’s internal fire

ANTONIO is the heart of the unknown mineral

ANTONIO inseminates the stars

ANTONIO is Pharaoh and Inca Emperor

ANTONIO is born of the night

ANTONIO is revered of the heavenly bodies

ANTONIO is more beautiful than Memnon’s giants at Thebes

ANTONIO is seven times bigger than the Colossus of Rhodes

ANTONIO encompasses the entire history of the world

ANTONIO’s majesty exceeds the magnificent sight otherwise known as the raging sea

ANTONIO is the whole Dynasty of the Ptolemies

All of Mexico grows around ANTONIO

Translation is a transformative experience, and translating the work of César Moro has taught me how to express Eros through poetry: writing sex can be as pleasurable as having it.