Diffracting Translations

Traductions de Chiara Montini (Français), Elena Basile (English) et Letizia Rostagno (Deutsch)

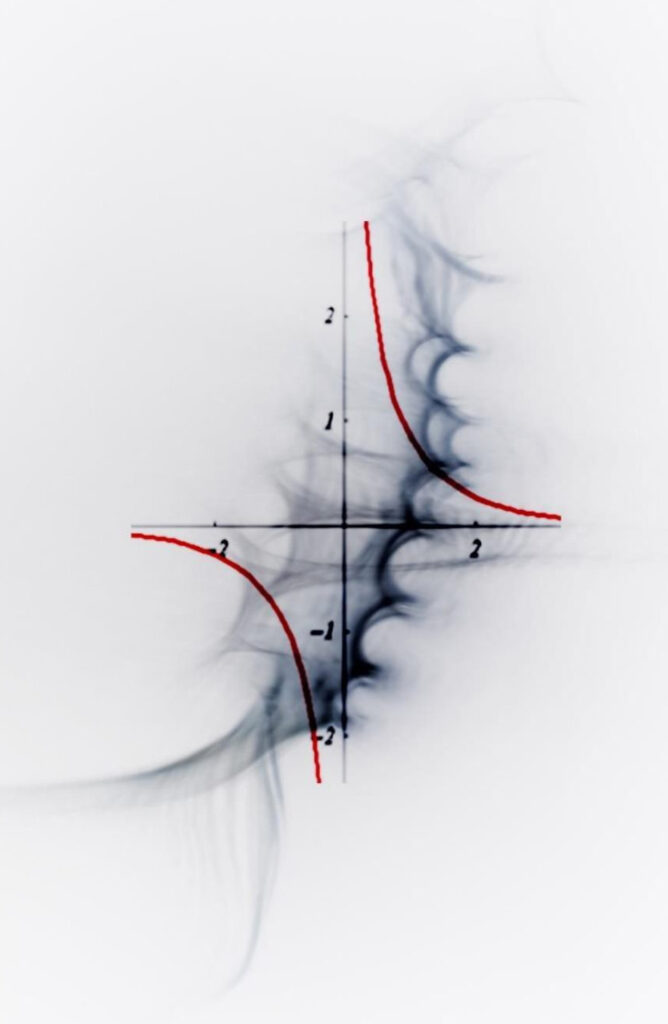

Cosecante Iperbole

by Angela Marchionni

Translating Angela Marchionni’s Cosecante Iperbole

The poems presented in this suite are excerpts from Cosecante Iperbole, a collection of poems by Italian artist Angela Marchionni, which sings of the grounding resilience of love and nurture in the face of the devastating impact of a culture of relentless consumption, presently playing havoc with the planet and its future.

Written in the aftermath of a protracted illness and the sudden loss of two friends who had been companions on an intimate journey of healing, Marchionni’s poems enact a generative conversation between the abstractions of mathematics and the polysemic openings of poetic writing, in an effort to loosen their entanglements with the most devastating vectors of contemporary technological and economic reasoning. The vicissitudes of a body vulnerable to pain, disease and the educated guesswork of biomedical protocols constitute the

experiential backdrop of each poem, whereas a grounded sense of the deeply enlivening and relational dimension of aesthetic experience orients each poem’s discernment towards building worlds governed by an ethic of responsive care rather than consumptive use.

Marchionni is a multifaceted artist active in Bologna since the early 1980s. Her art practice spreads across multiple fields, including theatre, visual art, sculpture, multimedia installations and poetry. More so, her generative and collaborative approach has been crucially important to a number of long-standing cultural projects, including early contributions to Il Teatro del Guerriero, a major feminist theatre company active in Bologna in the 1980s and 1990s; the founding of Beatrix V.T., a feminist collective and artist book publisher active in the 1990s and early 2000s; and, most recently, a standing collaboration with artist Letizia Rostagno, with whom she has mounted many collective exhibitions and has published early excerpts of Cosecante Iperbole.*

The title of the collection – which can be translated both as Cosecant Hyperbole or Cosecant Hyperbola – creatively deploys the language of trigonometry to map out the unfolding dynamics of nurture between living beings in asymmetrical relations of reciprocity and exchange with one another. Writing about the origins of the title, Marchionni recently explained that nurture, in its most basic mammalian model of a breast (seno in Italian) offering milk and a mouth sucking at it, can be diagrammed by the trigonometric function of a hyperbolic cosecant, that is, the set of points whose distance from two fixed points, or foci, remains constant (hyperbola) that applies to the reciprocal of a sine (cosecant). In Italian the word for “sine” is “seno,” which also means breast – hence the implicit overlaying of the abstract trigonometric function onto embodied relations of nourishment and growth.

Marchionni’s pointed use of “Iperbole” as noun rather than modifier also gestures to a further layer of poetic resonance. In rhetoric, a “hyperbole” – etymologically, a “casting” or “throwing” (“bole”) “beyond” (“hyper”) – denotes a figure of speech that deploys excess or exaggeration for the sake of emphasis. Contrary to English, where a vowel switch allows us to distinguish the trigonometric function of the “Hyperbola” from the rhetorical figure of the “Hyperbole,” in Italian the same word applies to both math and rhetoric: “Iperbole.” The use of such word, then, as simultaneously a mathematical and rhetorical noun, underscores the relation of generative excess at play in the nurturing exchanges of the living, such that they cannot be reduced to the formulaic idea of exchange as a symmetrical relation between equivalent values – this latter being the formula governing commodity exchange, whose toxic and deadening influence permeates contemporary consumer culture worldwide.

Marchionni’s poetry has a particular rhythm to it, one that may be best described as a tumultuous cascading of images spilling onto one another in ways that are as deeply defamiliarizing as they are astonishingly insightful once the radiance of their multiple connections becomes perceptible.

Dazzlement and disorientation constitute my reactions to every first reading, as frequent enjambments and syntactical distensions that stretch sentences into surprising shapes force my mind to grasp at straws while I drown in the musical flow of the stanzas. When I turn to the thought of translating these pieces, an aggressive impulse to parse out each line in a quest to stabilize meaning invariably follows – the challenge of the task dawning on me like a tight cage suddenly sprung up around me and the poem. Then the back-and-forth negotiations of sense and sound begin, with such patient sifting eventually giving way to emerging new patterns and possibilities in another language.

As we know, the imperative towards equivalence (i.e., the fiction of a zero-sum game of substitutions between one language and another) shapes the outer contours of the process of translation in much contemporary practice. And yet, despite its normative hold, equivalence cannot exhaust the ongoing effects of transformative displacement that emerge every time a new translator applies her deep reading and writing skills to a text in transition between languages. These effects may be more accurately understood as diffractions than equivalences, insofar as they bear the traces of patterns of interference, amplification and boundary-making that tease out sense-making as an open-ended and constantly recontextualizing activity.

Every translation, in the end, bears the traces of the singularity of a reader’s own engagement – what stands out, what doesn’t, what seemingly goes without saying – and then what constitutes at first an insurmountable loss and the strategies for getting around it. Remarkably, beyond each translator’s singularity, the multilingual translations presented here also bear the traces of intense communal conversations, as Chiara, Letizia and I met regularly over Zoom for more than a month to workshop our texts. These extended conversations not only produced an unprecedented deepening of our understanding of each poem, but also instigated lateral conversations between the languages, such that they authorized creative swerves that we may not have considered otherwise. In the spirit of ellipse’s invitation to expand beyond the traditional representation of translation, the pages that follow offer a visual rendition of all the interpretive hesitations, discoveries and choices we made before, during and after our conversations. Each of our English, French and German versions, then, now diffract the Italian lines, extending and twisting each poem into dynamic new possibilities, for new readers to enjoy.

Toronto, November 2020

Elena Basile

* Il paesaggio nel tempo. Evocazioni, manipolazioni, condivisioni. Art exhibition catalogue and book curated by Letizia Rostagno. Poetry by Angela Marchionni and by Marina Moretti. Loiano (BO): Edizioni Beatrix V.T., 2013.

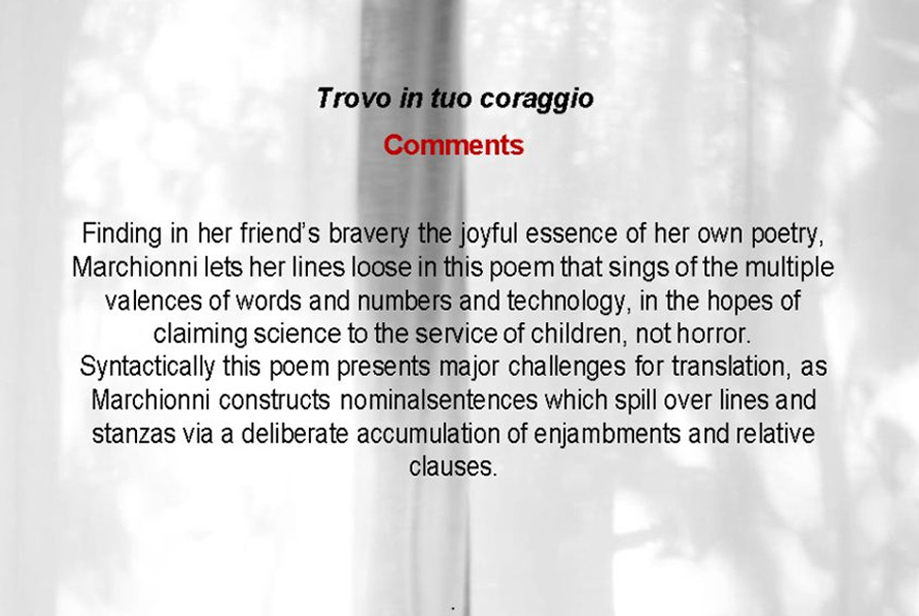

Je trouve en ton courage

la joie essence de ma poésie

cette poésie mienne

irremplaçable qualité qui défie

concourt (avec)

la parole effrénée dans la grâce parfaite

de la simplicité. Plus complexe

empreinte du son le morphème qui change et

égaye le plaisir des signes non restreints

au volume de l’inconnu qui universe

ignorance sur le nombre qui ne sait pas compter.

le compte de ceux qui ne savent pas compter

Si ensuite tu l’effleures de formules il recouvrira des cahiers

de polymorphes signes non encore arrivés sur la ligne

en poliphèmes engins de souffrances en variables d’absurdes

atrocités. Extraordinaire ! Battre les mains à cette

science qui se consommera pour réapparaître

consumera

sous un semblant d’enfance et non d’horreur

sous un aspect

Ah ! quelle horreur l’erreur d’avoir la foi!

concourt (avec) – Je serais tentée de ne pas ajouter la préposition qui manque dans l’original et crée l’ambivalence.

universe – Si l’ignorance est bien universelle, alors je garde « universer ».

le nombre qui ne sait pas compter – Pas la peine d’expliciter, il me semble, tout le monde sait qu’un nombre ne sait pas compter, mais il compte.

I find in your courage

the joy essence of my poetry

inalienable quality that relates to

competes with

the word unrestrained in perfect grace

of simplicity. A more complex

trace than sound is the morpheme that changes

of

and rekindles the pleasure of signs not restricted

to the volume of the unknown that pours

universal ignorance on the number that knows not how to count.

And if you caress it with formulae, it will cover notebooks

with polymorphous signs yet to cross the finish line in

Polyphemous devices of suffering in variables of absurd

one-eyed atrocities. Extraordinary! To clap your hands at that

science that will wear away to reappear in

semblance of childhood, not horror.

Ah! What horror the error of having faith!

Relates to/competes with translates “compete,” which Marchionni deploys as a transitive verb directly connecting it to “la parola” (“the word”). It is a syntax bending move that allows Marchionni to condense two very different meanings of the word into one. The double option I offer in English makes those two meanings explicit.

More complex trace than/of sound – there is ambiguity in the Italian “più complessa orma del suono”, as to whether “del” is genitive or comparative. Is the morpheme a more complex sign than sound or is the morpheme a more complex sign of sound? English forces a choice upon you, Italian does not. I choose both.

Pours universal ignorance translates “universa ignoranza” and attempts to capture the polysemic valence of “universa,” which functions both as verb and as adjective (“to universalize” and “universal”). One can read “versa” (“pours”) inside “uni-versa,” hence my solution, which retained the adjective “universal” and at least part of the verb “uni-versa.”

Polyphemous. I hesitate between leaving the implicit reference to the mythical one- eyed monster slain by Ulysses or rendering the reference explicit and just leave one eye in the fray.

Ich finde in deinem Mut

die Freude, Essenz meiner Poesie

Unverzichtbare Eigenschaft, die mit dem ungezügelten Wort

unveräußerliche

konkurriert, in der vollkommenen Gnade der Einfachhei.

Komplexer Fußabdruck des Klangs ist das Morphem, das sich

ändert

und das Zeichenvergnügen nährt, nicht

aufheitert

durch die Massnahme des Unbekannten geschränkt,

das Volumen

welches das Unkenntnis verbreitet, über die Zahl die nicht

zählen kann.

Wenn du es dann berührst,

es wird Notizbücher mit Formeln abdecken

mit polymorphen Zeichen, die noch nicht die Ziellinie erreicht haben,

in polyphemen Geräte des Leidens, in Variablen von absurden

Gräueltaten. Außergewöhnlich! Beifall für

jener Wissenschaft, die sich abnutzen wird, um in der Gestalt der Kindheit wieder aufzutauchen, nicht des Grauens.

Ah! Was für ein schrecklicher Fehler, Glauben zu haben!

Unveräußerliche vs unverzichtbare : ho scelto unverzichtbare, il cui senso (indispensabile) è più vicino a irrinunciabile. Entrambi sottintendono al limite una possibilità di scelta, mentre il termine Unveräußerliche (inalienabile), no.

Aufheitern vs nähren : al senso di rallegrare (aufheitern) ho preferito il »nutrire » (nähern) il piacere.

Massnahme vsVolumen : la parola « misura » abbinata all’ignoto mi sembra dia più l’idea sia del peso fisico misurabile o no, che del peso concettuale.

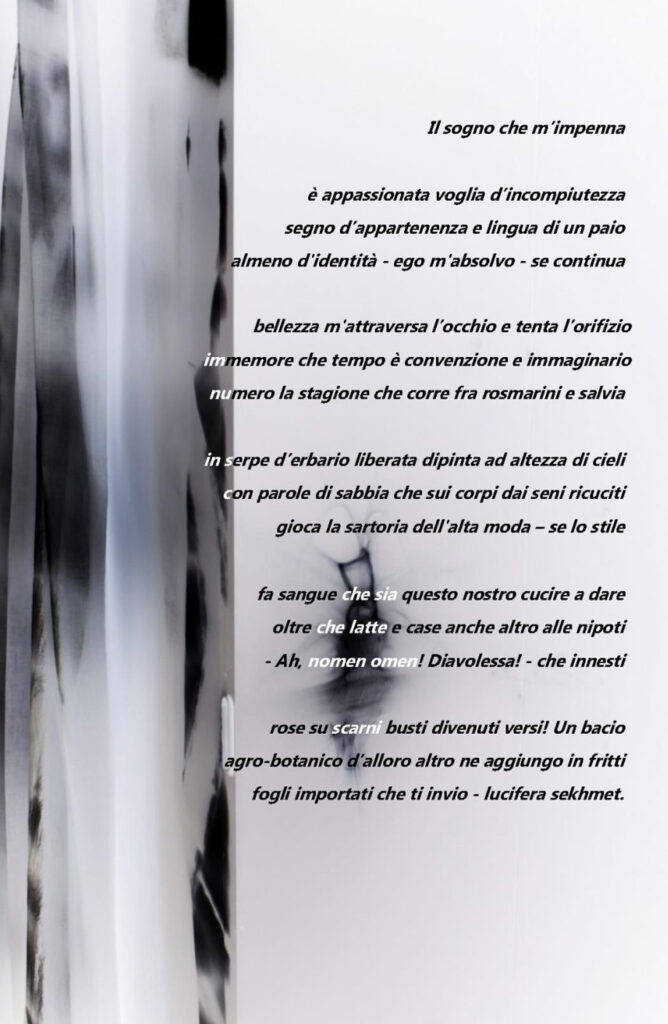

Le rêve qui me fait flamber

est désir passionné d’incomplétude

signe d’appartenance et langue d’une paire

au moins d’identités – ego m’absolvo – si continuelle

beauté traverse mon œil et tente l’orifice

sans mémoire que le temps est convention et nombre

oubliant/oublieuse ?

imaginaire la saison qui court entre sauge et romarins

romarins et sauge

en vipère d’herbier libérée peinte à hauteur des cieux

couleuvre/serpent

avec des mots de sable qui sur des corps aux seins recousus

paroles?

joue la haute couture – si le style

fait sang qu’il revienne à notre couture à donner

que ce soit à cette couture qui est la nôtre

autre chose que du lait et des maisons à nos petites-filles –Ah, nomen omen ! Diablesse ! – qui greffe

des roses sur des bustes décharnés devenus vers ! Un baiser

transformés en vers

agro-botanique de laurier j’en rajoute dans

des feuillets frits importés que je t’envoie – lucifère sekhmet.

d‛importation

Pourquoi, pourquoi « m’ » et non pas « me » ?

vipère Que faire de cette « serpe » ? « Covare una serpe in seno », comment dit-on en français ? [Réchauffer une vipère dans son sein] Ici la « serpe », vipère, me fait penser au fil utilisé pour coudre la coupure après une chirurgie ou une ablation du sein. C’est aussi le

serpent de l’arbre adamique – à hauteur des cieux ?

On revient à la nourriture, ces feuilles contiennent de la friture. Ou bien s’agit-il d’une coquille ? Des feuilles « denses », (it. « fitte ») ? Un

« r » se serait-il échappé ?

lucifère sekhmet Je découvre que c’est le nom d’une chatte. Serait-ce elle qui a volé (deplacé) le « r » ?

The Dream to which I rise

that makes me soar

is a passionate urge for incompleteness sign of belonging and language of two

identities at least – ego m’absolvo – if constant

beauty cuts across my eye and tempts the orifice oblivious to the fact that time is convention and imaginary

number is the season that scurries between rosemary and sage

in the garden’s serpent released and painted to heaven’s heights with words of sand playing with sartorial elegance

threading

upon bodies of stitched-up breasts – if style

draws blood, may our stitching be what gives more beyond just milk and homes

– Ah! Nomen omen! She Devil! – you graft

roses on bare torsos become verse! Here’s my kiss of agri-botanic laurel and more sent to you

in fried sheets of imported paper – lucifera sekhmet

Ego m’absolvo – I left the Latin here, since Marchionni plays on a well- known Christian formula for absolution given to the dying up until the Second Vatican Council of 1962 (“ego te absolvo” or “I absolve you”), by switching pronouns and having the I directly absolve her own self.

In the garden’s serpent translates “in serpe d’erbario”. The serpent in this stanza has great symbolic resonance, as it simultaneously refers to the biblical serpent of the Garden of Eden and the snake wrapped around the staff of Aesculapius, a widely used symbol of medicine; furthermore, the image of its scurrying across seasons morphs into a metonymic thread of sand-words, stitched-up bodies and sartorial skills (Marchionni uses crochet patterns in her cement sculptures) in the following stanza. It was hard to translate “erbario” in English, as “herbary” would not have strong resonance for an English reader, whereas “medicinal garden” was a mouthful and I needed economy in the line. I opted for just keeping the reference to the ‘Garden’ and leaving it to this commentary to expand on its significance.

Laurel. The stanza plays on the double valence of ‘alloro’ in Italian, as both the poetic ‘laurel’ and the aromatic herb ‘bay leaf’. Since the reference to “fried sheets of paper” makes the kitchen context clear, I opted for the poetic ‘laurel’ in English.

Der Traum, der mich erhebt

begeistert

ist leidenschaftliche Wunsch nach Unvollständigkeit

ein Zeichen der Zugehörigkeit und Sprache zumindest eines Paares

Identität – ego m’absolvo – wenn andauernde Schönheit

anhältende

Mir durchs Auge geht und sich an der Öffnung wagt,

vergesslich dass Zeit Konvention ist, und eine imaginäre Zahl

undenklich/unbewusst

ist die Jahreszeit, die zwischen Rosmarin und Salbei

verläuft, in befreiter Herbariumsschlange, auf Himmelshöhe gemalt

unddie mit Worten aus Sand auf den Körpern mit aufgenähten Büsten

die Haute-Couture-Schneiderei spielt – wenn Stil

Blut ist, lass unser Nähen,

neben Milch und Häusern, auch Anderes zu den Enkelinnen geben

-Ah, Schicksal des Namens! Du Teufel! – Du verpflanzest

Nomen omen

Rosen auf dünnen Büsten zu Versen verwandelt!

nackten

Ein agro-botanischer Lorbeerkuss, eins mehr füge ich hinzu in gebratenen importierten Blättern, die ich dir sende – lucifera sekhmet.

Erheben = sollevare Begeistern = ispirare

Andauernde = permanente, persistente / Anhältende = arrestare, fermare, sospendere

sich an der Öffnung wagt = che si azzarda sull’apertura, che osa l’apertura / die Öffnung versucht = tenta, prova, esperimenta, ma anche nel senso di tentazione

vergesslich = smemorato / unbewusst = inconsapevole oppure undenklich = che non ci pensa

Il est temps de donner de la lumière

aux chambres hospitalières de l’ange

à l’anguille qui tenaille le flanc

dans la matière aérienne de chaque amant

de miel et fondre l’aventure advenue

du mal au repos du sommeil.

Time to give light. “È tempo di dare luce” could also be translated, with a little prepositional nudge, as “time to give birth” (“tempo di dare alla luce”). I played with such option for a while, since giving birth can be read as part of nurture, a crucial theme in these poems. The angelic rooms of the poem, however, convinced me otherwise.

To the angel’s hospitable stanzas, “alle stanze ospitali dell’angelo.” I was serendipitously nudged towards using the word “stanzas” in English by Letizia’s hesitation between her own choices in German, which oscillated between “raum” and “zimmer”. Her explanation of the distinction between “space” and “room” at play in the two German words, each of which captures only one connotation of the Italian “stanze” made me question my initial unproblematic English translation of “stanze” with “rooms.” It occurred to me that “stanze” in Italian has its own polysemy, since the word can also refer to a group of verses in a poem… a ‘stanza,’ precisely. So, I made the translation swerve towards “stanzas,” which keeps the Italian sound while veering towards something that is only faintly perceptible in Italian, but nonetheless there.

Time to give light

to the angel’s hospitable stanzas

to the hospitable stanzas of angels to the hospitable rooms of the angel

to the eel that grips the hip

in the delicate substance of each lover’s

in each sweet lover’s delicate

sweetness and dispel the spent venture

substance

of evil in slumber’s rest

The two alternative translations are attempts to sound out the same line with

(a) a plurality of angels and with (b) a more prosaic “room” for their dalliance.

Es ist Zeit, Licht zu geben

zu den gastfreundlichen Räumen des Engels zu dem Aal, der die Flanke fasst

in der leichten Substanz eines jeden Liebhabers

von Honig und das geschehene Unterfangen des Übels

Schicksal

im schlafenden Ruhe zu schmelzen.

auflösen

Liebhabers von Honig / Honigliebhabers Il primo mantiene di più l’incertezza che per l’italiano è più sottile

Unterfangen = impresa. Altra possibilità Schicksal= destino

Schmelzen ha più una connotazione di dolcezza che fa il paio con Honig.

Auflösen che ha significato di sciogliere, risolvere, scomporre non ha la stessa dolcezza di significato e di suono

Théorème du téléphone portable

si par hypothèse ton téléphone portable ne coûte

que le prix du rapport non entre toi et ton besoin

d’amour mais entre la connaissance et notre chimie interne

s’il est illusoire de croire tienne la liberté – qui devient commune quand

cette liberté tienne

un même produit déséquilibre l’air qui se fait parâtre

et qu’on l’admette partagée par la même

confrérie en distractions quotidiennes d’actions à la hausse

le jeu au rabais l’escargot de l’oreille – conque

l‛imposition cavité

dressée en système qui régit des réponses

d’amènes scissures à dominante hémisphérique (dendrites

et glutamate perdus en Lucia par voie de voiture au fond de sa vie

par voie (d’) auto avec sa vie

Alors que le vivant ne vive

ni d’arrogance, ni de profit.

L’air, en français, est masculin. Ce sera donc : parâtre. Marâtre et parâtre, mots tellement désuets, en français, où les parents s‛alternent plus rapidement qu‛en Italie. D‛ailleurs, ils deviennent « belle-mère » et

« beau- père », rien à voir avec les images négatives qu‛évoquent les termes en italien, matrigna, patrigno.

Theorem of the cellphone

Let us assume that your cellphone is paid for by the simple cost of the relation not between you and your need

for love but between knowledge and our internal chemistry

and be it illusion to think of freedom as yours only – it becomes common when that very same phone unsettles the air

and turns it mothrignant – and let us further admit it as shared by

the same fraternity in constant distraction of climbing shares, forcing into recession the ear’s cochlea – cavity that grows into a system that governs responses

of agreeable fissures in hemispheric dominance (dendrites and glutamate lost in Lucia via car with her life) The result be that the living live not of ignorance

nor of arrogance or profit

cell phone – I kept the cell separate from the phone, since the poem digs deep into the cellular dimensions of our being.

mothrignant translates “matrigna” (‘step-mother’) by combining ‘mother’ and ‘malignant’ (which the poem infers is the quality of the air degraded by the cellphone’s electromagnetic radiation, and which in Italian would read “maligna”).

Handy Theorem

Nehmen wir an, dein Handy war zu den einfachen Kosten der Beziehung bezahlt, nicht zwischen dir und deinem Liebesbedurfnis,

sondern zwischen Wissen und unserer inneren Chemie

Und nehmen wir an, es ist eine Illusion zu glauben, dass die Freiheit dein(e) sei –

was häufig wird, wenn dasselbe Produkt die Luft, welche Stiefmutter wird, aus dem Gleichgewicht bringt – und geben wir zu

dass von der gleichen Bruderschaft geteilt wird,

in täglichen Ablenkungen von Aufwärtshandlungen, das Aufdrängen der Ohrmuschel nach unten –

Hohlraum, der zu einem System wächst, das Antworten regelt

von angenehmen hemisphärisch dominanten Spalten (Dendriten und Glutamat verloren in Lucia im Auto mit ihrem Leben)

Das Ergebnis ist, dass die Lebenden nicht in Unwissenheit leben weder Arroganz noch Profit.

Wissen = ha più connotazione di scienza che di consapevolezza (Bewusstsein)

Traduire Cosecante iperbole d’Angela Marchionni

Tout, dans la poésie d’Angela Marchionni, est contraste.

Contraste entre le mot et la parole. Contraste entre une syntaxe établie et une licence « poétique ». Contraste entre une association qui serait spontanée et une autre, moins évidente mais non moins vraie. Contraste entre un sujet singulier (qui peut être un « je » ou un « tu ») et un « nombre » indéfini, la masse anonyme où tout un chacun se confond, « ceux qui ne savent pas compter ». Et, par conséquent, contraste entre le vieux sens – commun – et le nouveau sens – individuel – que la poétesse recherche et souhaite transmettre. Contraste encore et toujours entre une poésie qui vise à la complétude et une science qui aspire à l’exactitude. Les deux vouées à l’échec.

C’est là, dans cet échec, dans la vie imparfaite, que les deux éléments de tous ces contrastes se rejoignent et se complètent. L’absence des virgules, qui rend parfois la lecture ambiguë, renforce leur (comm)union.

Le mouvement des textes d’Angela Marchionni est une fuite en avant, la crue d’une rivière qui traîne dans son chemin toutes ces particules en apparence incompatibles. Elles se mélangent, détritus d’une lutte sans merci. Ces détritus – les mots ? – sont travaillés comme au crochet, l’un s’accroche à l’autre. Ainsi se compose la trame de chaque poème. Pour ce faire, Angela Marchionni met en scène un jeu sur l’ambivalence et l’ambiguïté des mots, des signifiants, des syntagmes.

La syntaxe n’est pas immédiate, elle confond les pistes et n’aide pas le traducteur qui aurait le devoir tacite (mais auquel nous voulons parfois nous opposer) de ne pas violer la langue cible, la langue de la traduction.

Ce sont nos travaux, le fruit d’une collaboration avec Elena Basile et Letizia Rostagno, plus un coup de p(o)uce de Patrick Hersant,* qui ont donné forme, une autre forme, sans doute, où nous avons déployé ce jeu poétique de renvois, d’enchaînements, d’unités éparpillées.

Paris,

Novembre 2020

Chiara Montini