Hot Chocolate (a scene from Goodbye, Ramona) by Montserrat Roig

Megan Berkobien & María Cristina Hall

Commentary:

***

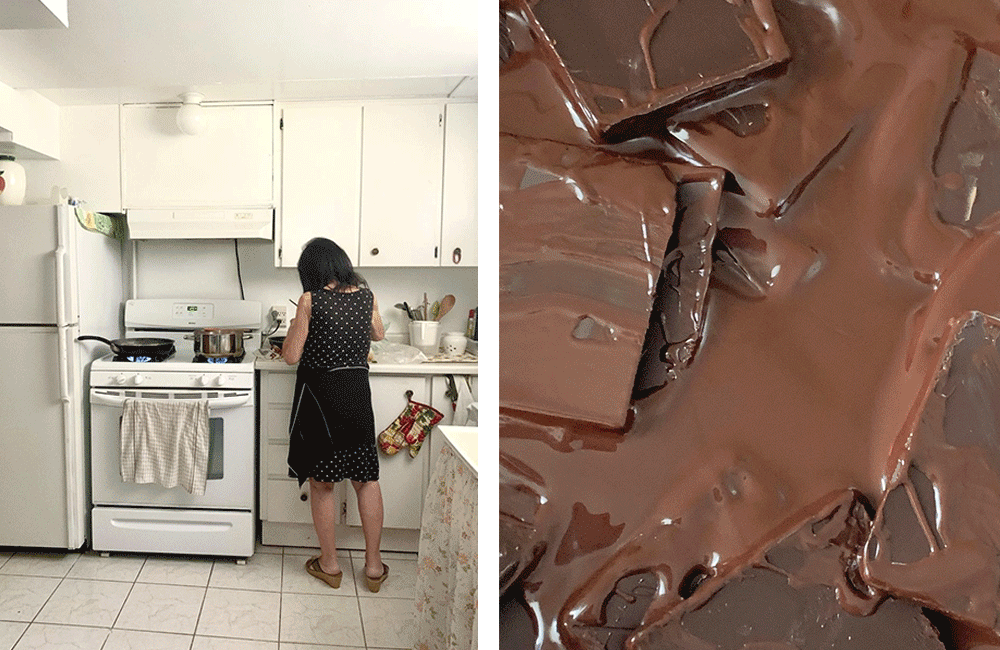

They’d proclaimed the Republic and now everyone was saying that they’d seen it coming. The two Mundetas couldn’t find Father Pere, their confessor and family friend. The vicar told them that he’d left at nine that morning and had yet to return. Mother pulled herself together and said, let’s go to Núria’s. Mundeta was tired and craving her chocolate and melindros — such thick, hot sap, so firm it was almost solid. She’d dip each melindro, bit by bit, carving out this circle then that, and the circles would broaden concentrically, and she’d submerge the melindro as if she herself were diving in. She’d slurp the chocolate to its very last drop.

When they got to Núria’s, the women’s instrumental trio was nowhere to be seen. La Rambla was teeming with people and they could hear a dull rumble from their seats at Núria’s. Patrícia was there, anxious and flighty as a wingless bird. As was Aunt Sixta, who kept chewing on her gloves uneasily. Aunt Sixta had dolled herself up, but she had no taste when it came to dressing. Today, in a show of careless affectation, she had donned a blue velour coat of sorts that Mundeta’s mother had turned her nose up at, even to go to Bar Glacier. Kati laughed in her face; she had no taste. Kati, a savante like none other, with all kinds of foreign friends, the French being her favourite, always said she “lived for the day.” She’d enjoy poking fun at the types of people who went to Núria’s, and Mundeta Ventura would have to put up with all of it. That so-and-so’s trying to look like Ronald Coman, poor thing, but he’s thin as a rake, that so-and-so’s moustache is scraggly like a little rat’s tail, that the young woman who just walked out was donning a satin headscarf that could have been her grandmother’s. She was so exhausting, Kati — cocotte on the one hand, reverend mother on the other. She kept repeating the word chic while casting Mundeta ironic looks. The other women spoke poorly of Kati, but they’d invite her to their luncheons and parties all the same because she was so up to speed on the monde. All Valldoreix jumped on her for going to Casino de Sant Cugat by herself, and especially for her brazen behaviour toward the other sex. The only one who was somewhat close to her, albeit superficially, was Mundeta’s mother. Both enjoyed reading and often exchanged books, preferably romantic poetry and the biographies of queens. But they all secretly envied Kati. Her way of vivre sa vie and being independante made them itch a little. She was thirty, single, and lived on her own. She threw parties in Valldoreix, innocent parties, sure, but the rumours took them to new heights. On quieter days, Mundeta would delight in Kati’s waxed, barely-there brows. The slender, hasty line she’d trace over each one gave her a look of constant exasperation.

Mundeta gazed at the chocolate before her. It still seemed to boil, full of gurgling little bubbles. Patrícia, with her Aromas of Montserrat liquor, and Aunt Sixta, with her Arnateu grape must, brooded, yelled, and prattled non-stop, without catching a single breath. Patrícia worried about Esteve, who had gone to Plaça de Sant Jaume, and Kati teased her for it. She was making jokes in bad taste, jokes Patrícia didn’t get. Mundeta swirled her melindro this way and that. It would sop up the liquid so nicely, dripping a little, and she’d scoop up the little drops, which then slid down her tongue. She could hear her mother saying the same things about her as always, that Mundeta hadn’t wanted to come to Núria’s by herself, that she’d never marry. Kati said, I think she’s too naïve, too childish, what’s there to say, you need to get with it. That’s right, she’s got to get with it, Aunt Sixta added, downing her Arnateu in one fell swoop. She’d take the tip of her napkin and dab herself softly, tracing the edges of her lips. Two red blotches remained on either side of her mouth. I have to get with it, I have to get with it, and the chocolate oozed down her throat, softly, warming her bosom, dripping down further and further until it tickled her legs. And Mother said, tell me about it, you have no idea how much I fret over her, she’s such a scrawny little thing, and so shy. She’s lucky to have you, Aunt Sixta noted, her gloves moist. You’re twenty-two, chérie, don’t you like boys? Hush now, Patrícia said, that’s counterproductive. And the chocolate, the chocolate, the fleeting aroma of chocolate. I should order another, since I have to get with it.

And the conversation started taking a turn — finally they’ll leave me be, just me and my chocolate. They were saying that Plaça de Sant Jaume was packed with people. And Patrícia said, they’ll kill my Esteve, he’s so reckless. My husband’s quite depressed, Aunt Sixta said, he’s in the Patriotic Union, you know. He’s scared; he thinks we’ll all be in for it, with Primo de Rivera at the very least. I don’t know, Mundeta’s mother hesitated, I have a feeling all these changes are for the best. I think there’ll be luckier times ahead. So do I, Kati added.

Mundeta couldn’t figure out why her mother had gotten so flustered, why she’d been panicking just an hour earlier. Her mother was mercurial, changing her mind from one moment to the next; she’d become infatuated with people and love them to death, but the next day she’d forget about them completely. She contradicted herself. She seesawed from happy to sad, from dread to fortitude at the drop of a hat. Sometimes they’d walk down La Rambla — since her father had died, she hadn’t wanted to go back to Passeig de Gràcia — and a strange languor would take hold of her. I feel melancholy, she’d say, my heart hurts, and she’d turn white as snow. At times she’d become overwhelmed with terrible premonitions and she’d let her mind wander for an entire afternoon. Adjectives like “evanescent,” “subtle,” “languid,” and nouns like “love” and “fortune” were her darlings. She’d jot down her favourite verses in her notebook, and she’d never let them go. She’d evoke Siruana’s wild, tempestuous landscape in lugubrious tones, and she’d tell the saddest of tales. Tales of love. If they went to the movies and the film moved her, especially Amanecer and El Caid, she’d sigh the whole time. But Mundeta had never seen her cry. Her favourite place for a walk was Parc de la Ciutadella, especially in the fall when Barcelona was overcast, the rain and dry leaves carpeting the ground. She’d find the loneliest spots and spend long stretches there, sitting on a bench, cloaked in the evening fog. Mundeta would follow her as she stopped, fascinated, here and there, at the water-lily island or in front of the waterfall. And she’d tell her how the people in Barcelona used to go to the caves under the waterfall and jump off to kill themselves. And that was why they’d put up a fence. But Mundeta wasn’t listening because it was so cold at the park that the skin on her face would flake.

She kept her eyes glued to the street as she listened to the women’s exchange, peppier today. The chocolate was thick and the melindros plunged in deep with pleasure. Today, lunchtime at Nuría’s was void of conversations about how to make hake filets a la condal, or about the miroir at the Baltà house, or that radio commentator Toresky’s latest fancy. Nor could one hear that common succession of idioms, no what can I say, no the way things are going, I can’t trust a soul, no men should be kept on their toes, no victim-wife and savage, shameless husband, no we women are birds of a feather, right? Nothing about the maids, who put on more ladylike airs by the day, nothing about the new confessor at the Jesuits who can really touch you with his speech, who really understands the feminine soul. Mundeta made her way through the melindros one by one, practically devouring them as she dipped each by just one end, leaving it half dry, half soaked. The women interrupted each other — what a day it was already. The events of the Republic had made this traditional lunch more amusing. If she swirled the chocolate slowly, in spirals, it would thicken and take on darker hues. Today she wouldn’t have to listen to marriage advice from Mother, Patrícia and Aunt Sixta. Kati never offered marriage advice, but she entertained herself by rubbing Mundeta’s homeliness in her face. Honey, how can you be so dreadful at doing your makeup? Men choose with their eyes, they want beautiful faces, the aesthetic of a clean countenance. And isn’t a well waxed and nicely made-up face arousing!? Take your eyelashes and brows; they’re awful. You look like you rubbed them in castor oil and petroleum jelly. You should groom them with a small coconut shell; grind it up and mix it with sweet almond oil, dear. If you can’t muster up some vanity, just a little coquetry, you’ll grow wrinkly and dumb like an old maid. A man is a partenaire who wants sweet nothings, joy, spontaneity. Not all men, of course, Kati went on, you know I’m not interested in all men, just in the attractive, intelligent, adventurous ones. Men, these men. According to Patrícia and Aunt Sixta, passionate relationships brought nothing but disgrace, headaches. One harped on about how it was better to be an old maid and dress up the saints at church than to be in a bad marriage. The other said you can only trust a man as far as you can throw him. They’d recite entire passages of that Spanish-language book, La perfecta casada, a keepsake for the bride, a wife’s attentions. Pueden sacarse del libro provechosas enseñanzas, especially lessons putting women back where they should be: en el hogar. And of course, not a peep about slavery. Mundeta said they cited other people’s texts since they were empty inside. Boy, don’t I know it, Mother hasn’t ever cried. She thought that except for Kati, the other three women had let love in too soon. One should wait for love patiently, carefully. She’d do better. Of course, she hadn’t met one yet — a man. Love would come to her in the slow silhouettes of illusion, like boats docking at port. She’d lay her head on her beloved’s chest, like Jeannette McDonald rested hers on Maurice Chevalier, or Janet Gaynor, sweet Janet Gaynor, who found shelter in George O’Brien. She would walk the path of happiness with a sturdy, well-composed man by her side, someone who’d love her every night and remind her she was the only one for him. Under the linen sheets that would give off an irresistible scent of thyme, they’d swear each other eternal love, boundless passion. And a rush of kisses would possess her, day and night. Mundeta, what’s on your mind?

Ramona, Adéu was published by Fum d’Estampa