Excerpt from Epic of the Food and Drink of Chile by Pablo de Rokha

Christopher Winks

Beautiful as young cattle is the song of frogs stewed among partridges,

the tall blanket from Doñihue is lovelier than the loveliest lady’s legs, the loveliest thing there is,

for getting started on a nicely prepared curanto,

shrimp from Huasco is delicious, oozing wine and feelings,

like the honeyed mussels harvested among women, among oceanic bull kelp, among laurels and

vihuelas from Talcahuano for the autumnal lemon juice of the centuries.

and like the fragrant Colchaguan empanada, which widens the throat with heat and cries out

from the oven, peach blossoms flowering all around.

And what do you all say about pork ribs with garlic, real spicy, roasted on a wineberry spit, in

June, on the banks of the Peumo or the patagua or boldo trees which sum up the dramatic atmosphere of the rainy dusk of Quirihue or Cauquenes,

or about guañaca in goose broth, very much part of the Talca or Licantén family?

no, grilled quail is eaten the same way you listen to “El Martirio,” on the Aconcaguan slopes

and fried mullet in the Maule, where the silverside leaps upon the sacred frying pan of pleasure, completely smooth from the river, enriched on the Maule boat, while the Carreño girls, as if suffering, strive towards “the human” and “the divine” on the vihuela that’s been in the family for ages.

Huge turkeys smelling of summer that are autumns of walnuts or almost human chestnuts, I

eat them throughout the country, and in Santiago I kiss them,

like the earthenware jars where the chicha sighs like the prettiest girl in Rancagua lifting her

skirts beneath the parish apple tree, in the same way

as the shack with a wall made of chilcas where we drink from carved drinking horns a solid

aguardiente,

or love’s mattress where we sail and, sobbing, confront night’s terrible oceans, on whose

horribly tenacious blackness converges the bloody bellflower,

or the tear we raise to our lips when joyfully singing.

Wine from Pocoa is huge and dark in the evening of the Republic and when it’s in the heart

memory

and defense of heroism sing in the cut of the spurs like

the animal’s back, swimming in the fundamental song of the pools or against the foam’s red

uproar.

Well-aged chichita bellows in the general stores like a big sacred cow,

and San Javier de Linares will already be golden, like grilled meat, on April’s bloody highways,

autumn’s guitar will weep like a soldier’s widow.

and we’ll remember everything we haven’t and could have and should have done and wanted

to do, like a madman

leaning over the village’s empty well,

watching, with desperate volume, the horses of youth in the broad fusillade of dusk,

which collapses like a memory into an abyss.

The mount shines in Curicó, from sea to mountains, resounding like a wheat cart’s obstacle

course, resounding

like a cowherd or a thresher or someone chasing a calf, twirling the lasso

above a guffaw dripping sun of the task, where manure scents, godlike, the domestic dung

heaps, with huge black-widow spider’s eggs.

An impressive adobe house with a square patio, with orange trees, with a corridor redolent of a

distant age,

and where the distillery sings, drop by drop, the meaning of eternity in the water, recalling the

ancestors with its trembling cemetery pendulum,

exists, in Pencahue as in Villa Alegre or Parral, or Caleu or Putú,

though it’s the large village of Vichuquén which can take pride on, like the trough or earthenware pan, its Spanish lineage, cordilleran, and the entire coast, and the tonada-houses

of the Colchaguan and the Curicanos that express it in such an immense language,

eating Chilean meat rolls.

Because, if before dying on a rainy day you find yourself tiring of Chillán longaniza caressed with

rough wine, from Auquinco or Coihueco, bathing yourself in harp, guitar, and accordion, cutting outrageous capers or guffawing, savoring the bellowing spoonfuls of peppers and fried potatoes,

the same thing goes for sipping a dark Tuncana wine, in August, when the pigs look like bishops,

and the bishops look like pigs or hippopotami, and washing down the food with a few shots of sour-cherry brandy,

yes…in Gualleco the dumplings look like the local misses: wasp-waisted and sleepy-eyed, then,

ticklish and generous, they drop their shyness and let themselves be kissed, endlessly, on the mouth.

And the fried, well-spiced empanada and the sopaipilla, which moaned in flaming bacon, are

blessed between swigs at the foot of the Bio-Bio’s Patagonian oaks, wherein thunder rolls with wide whips,

but nothing equals the ringdove, savory in July’s stubble, in the absolute heat of that season,

among bonfires and tortillas, drinking from the barrel those immense wines smelling of gunpowder and friendship, or the vineyard-size thrush, which is lament’s agrarian dagger,

hunted among the sacred pompanos like a thief from the peasant neighborhood and which is

cooked in white fermented grape juice,

nor the causeo salad with fingerling potatoes, which should be eaten in Codegua, not after

drinking lots of chacolí with bitter oranges, but with wine from Linderos.

When ham is properly salt-cured, in the riverine solitude of Valdivia, and golden and lovely like a

Percheron pony or a beautiful tit of a nun resembling a bride

the poem of smoke’s spiritual saturation begins and just like the aromatic olives of Aconcagua,

with which alone it is possible to savor drunken ducks with celery and well fattened and doused in a hundred bottles, the aromatic olives of Aconcagua are marinated in brine from the Iloca salt mines, only the tasty meat of the buccaneers and pirates is smoked with actual smoke, but elmwood smoke from La Frontera and games and blows or a clash of ancient swords emerge,

and the spicy tripe Talquina-style is roaring.

In Tutuquén a Valdiviano soup has such fiery condiments as to summon up a long swig and, like

bean salad, it is seasoned with lemon and winter onion sprouts,

all of which, on the tablecloth, blossoms, with tortillas cooked in embers and also the roast

potatoes and chestnuts, like in Concepción, when mussel soup is made, or in Santiago, beef intestines or slaughterhouse cuisine, at the height of a winter’s day, or in Valparaíso, mussels, totally mussels, raw or grilled over peumo wood.

However, we don’t eat oysters in these surroundings, where fish stews shine and stand out, or

the banner of an incomparable Pipeño wine flames,

we eat them in a great metropolitan restaurant, with a generous mulled old amber wine from

the Maipo’s age-old grapes, we eat them during the rain raising our glasses in the heart of the storm,

as if we were going to be shot or hung at dawn in the trenches.

And in Constitución or Banco de Arenas, sea squirts are chopped with knives and bathed in

coastal lemons and white wine, as much white wine as the “white” in white wine, while the silverback’s presence displays its bloody sun,

like powdered gold on battlefields.

Because in Antilhue a longaniza as exquisite as Chillán’s flourishes, a longaniza that was eaten in

the vacant lots of the great funereal city and, like the bull of Miura, was the sole and definitive one.

that’s why I prefer the marinated loin seasoned in Lautaro or Galvarino or Temuco, obtaining it

with southern, oceanic pork,

and a big cauldron of turkey in Lonquimay or charcoal-roasted baby lamb, with quideñe

mushrooms gathered on the big mountain of Araucanian Copihual, in Traiguén, in Nacimiento, in Mulchén, Angol, and Los Angeles or on the same shore of the Vergara River or in Cañete or on the illustrious Gulf of Arauco, as for example in Lebu, and even on the epic spine of the Nahuelbuta Cordillera, Pedro de Valdivia’s mausoleum.

Ah! happy are those who know dark-skinned women’s caresses and stuffed sea urchin from

Antofagasta or guanaco jerky from Vallenar or Chañaral, tasting and savoring it like a girlie of fifteen Aprils,

in the mining sierra, among miners, strong and heroic, or conversing with the sacred mules that

forged the mines,

while two baby goats from Illapel joyfully disport themselves in the fabulous aromatic ashes of

the boldo tree of Chilean flags, glorious as glorious grape spirits.

The roguish roistering huasos from Doñigue or Machali or San Vicente de Tagua Tagua or Peumo

or Quivolgo eat prairie oysters grilled

with skin on, from beginning to end of the October rodeo, among quillay or the flowering raulí

of the “half-moons,” shaken by the national bellowing of the cattle, shaken

by the courage of the rural horsemen and the sonorous sun,

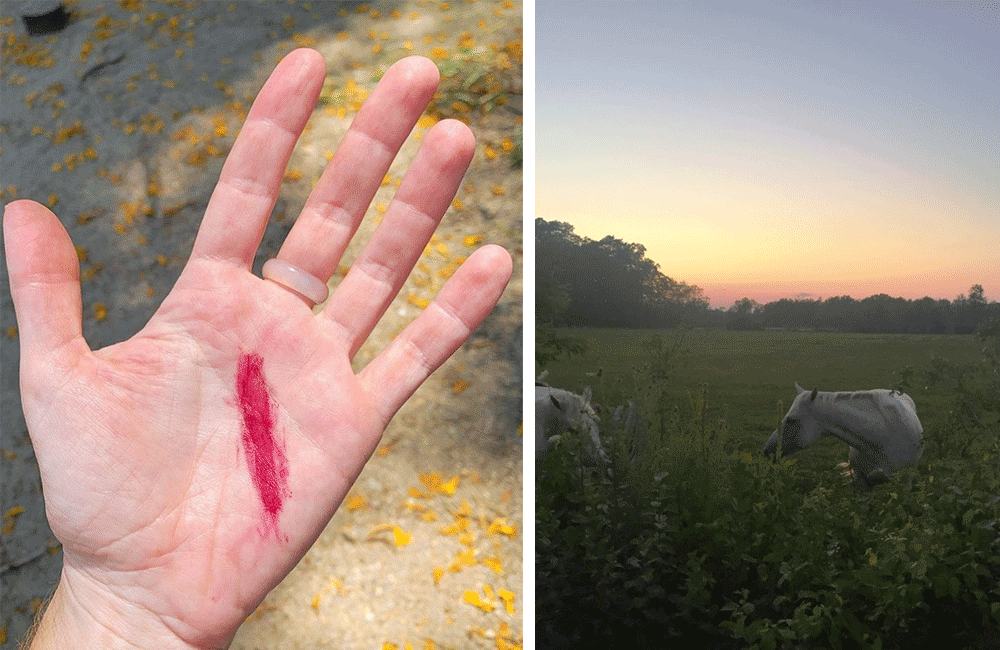

and they take their ñachi hot, drinking it from the most incredible slaughter, like in the frightful

religious sacrifices of archaic faith, horribly bloodstained,

with nature and blood as gods.

If you prefer goose with garlic and chickpeas, eat it in the province of Cautín, and curanto in

Chiloé and Osorno or Puerto Montt or in Carahue, during the “holy” period of the Candelarias, on cloudy, invariably cloudy days, while fallen leaves shiver in the immense water.

Singing and drinking, the area’s public employees cross from one eternity to another, unshaven,

completely stuck into aguardiente, in those huge, yellow bronze cots covering the Central Valley of the Republic with blue clouds and cherubs,

and the teacher drinks his glass of torment, precisely in Pelequén, in Chimbarongo, in Bailahuén

or in Curanilahue with me.

The people from Curanilahue say that nobody, even the most knowledgeable and settled,

understands how to grill flank steak with beef round jerky soaked in toasted flour and oregano, other than the Curanilahueans,

but the people from San Clemente, if their surname’s Ramírez, disagree and add calf gizzard and

brisket with a superabundance of greens and vinegar,

and they reduce their bellies with guarapón hats and well-toasted hazelnuts from Culenar in

Maule, Maule Abajo, or with grilled cheese, the kind that smells of Cuyan Coironal or of “sadness,” sung by muleteers, over there at the “Shelter from the Sorrows,”

to which respond the denizen of Pichamán with half a calf cooked in alambique lees

and the peasant from Tanguao or Hinguanes with suckling pigs stuffed full of partridges on the primitive and criminal coals of the rubbings of May, which are like the embers of the ancestors and the first fires of the world.

The Licantén chanfaina is a lacustrine stew, a tale of river and riverbank, fluvial-oceanic and

cordilleran, regional, village, peasant and provincial and something like churchly, volcanic and dramatic,

and the soup of cusk-eel, prairie oysters, mussels, like dumpling soup, those are for the

boatmen, brothers of the Valdivian boatmen, who it seems found a large seagull swimming in the sacred, fundamental, and elemental broth of the marrow-filled cow-femur bones or in the boat of potatoes with luche seaweed or wild cochayuyo seaweed,

rather than charquicán stew from iodized algae, which restrains but depresses it, overcooking it like a dumbhead.

Udder cracklings, eaten by train engineers and railway workers, present themselves floured, on

the run, clandestinely, in the dives of the southern station,

along with the fledgling chickens, aflame with goat’s horn chili peppers or Chilean cheese,

grilled, with roasted garlic,

neighboring the imposing cow’s foot with large onions, subject to the ratio of the tortilla, which

recalls the braziers and chestnuts of August,

between the fat crab of the longitudinal train and the hard-boiled eggs for the journey,

and those tasty causeo salads of limpets and conches that the bays offer us, face to face with

the diverse sea of Laraquete, with the scent of coastal lemon, of the old village house with violets, Winétt, of provincial rain infinitely singing and weeping,

when we found ourselves completely alone and sleepless

and the orange drink with cheap moonshine, mischievous, demanded of us the ocean at its

most dramatic and romantic on a humble clay platter.

If possible, we served ourselves an empanada, real hot, piping hot, real spicy, under the grape

arbor, seated on huge stones, remembering and longing for things past and disparaging our relatives, dram upon dram of Talca cabernet, and the sopaipilla, raining, with a poncho, completely soaked, among oranges and guitars, accompanied by drunkards and the parish priest.

It’ll be tripe braided like a young lady’s hair, aromatic and comfortable as a widow’s thigh, warm

as virgin’s milk,

we’ll harvest it from a heifer or steer or calf, unmated, who if in love laughs and eats noisily,

choose the melancholy one,

let’s serve it with bounteous mashed potatoes, in shirtsleeves, at Renca or Lampa, accompanied

by obliging ladies and deep red wine, more than enough and a lot,

when hopefully the butcher’s name-day is celebrated or the saint’s day of the village cop

and the house’s little girl invites you to recite, like any “Pen Club” punk, for example,

so then…sing the national anthem, proclaiming yourself to all present

the Conquistador of South America, proclaiming yourself Captain of the American pirates,

proclaiming yourself an ancient and valorous Viking in retirement until daybreak, when

the birds of dawning sing the romantic-dramatic tears of the sunken moon,

we don’t know how we put our hat on,

nor the name of the dead-drunk guy from the muscatel winery.

Blessed are those who eat five or more kilos worth of hot roast pork,

in a San Felipe midwinter, if winter is thunderous and traversed by floods and lightnings

and he owns a large Castilian cape;

beneath it he shelters a guitar and the beloved demijohn.

And how the handkerchief waves

like the proud flag of a great ship, at nightfall, if the mistelas have a good head on them, if the

huasos are huasos and not tallow candles, if the punch is on fire and the cueca erupts

with the wild ones stomping, between heaven and world,

a man draws the writing of the fundamental manliness of Chilean working stiffs,

and a woman fixes the flight of flirtatiousness in her shoes,

for we’ve come to Peldegua to soak our Lent in chicha from the “Transit” in Peine

or we go around having fun, drinking, or making

the rowel of the spurs sing, or the golden tint of the lassos woven from the skin of a Las Condes

guanaco,

above the bullyboys’ chicken loin.

With a wineskin made from pony or goat, approach the rider with jerky, aguardiente, cheese,

and tortillas – never chicken, which is for the traveler, not the muleteer – be prepared when anticipating stirrup braces from Chillán with a container and a well-worked drinking horn, because a man wearing manly pants, traveling on horseback, won’t drink even red wine, no, instead a large hornful of fiery cane liquor

and he doesn’t live it up, because he gets entangled in his rags, but instead

after putting on his drainpipe pants, his jacket fastened with six rows of buttons and his pointy-

toed footwear for weddings.

Since absolutely all baptisms are celebrated between June and July or August, as well as vigils

and saints’ days and weddings, parties, in general, bashes, folk celebrations, surprise raids, gatherings, and to-dos, just like all idiots are named ALONE,

if your body aches, drink a big chupilca early in the morning and rub your hands with pleasure,

eat an ajiaco of pancutras and sausage meats and don’t drink your shot pure, drink it pure with

torrejas made of the most bitter-acid oranges you find, naturally in the village’s oldest orange tree,

wash yourself in strong and brave chacolí wine

and go throw that last walking stick in the air well before the grim reaper pushes your back up

against eternity and your breast face to face with the sky.