Excerpt from Treatise on Coffee, Tobacco, and Intoxicating Substances by Mustafa bn. Muhammad al-Aqhisari

Selma Zecevic

Should a Muslim Enjoy Coffee and Smoke Tobacco?

Law, Poetry, and Piety in Eighteenth-Century Ottoman Bosnia

When a Bosnian Muslim man of “high prominence” asked an eighteenth-century mufti (expert jurist), Mustafa bn. Muhammad al-Aqhisari (d. 1756) from Ottoman Bosnia, for a fatwa (an expert legal opinion) on the religious permissibility of the consumption of coffee, tobacco and intoxicating substances, the debate on the legal status of these commodities had already subsided in other parts of the Ottoman Empire: While generations of jurists before al-Aqhisari found unambiguous evidence concerning the prohibited status of wine and other intoxicating substances, they could not provide the same for coffee and tobacco.

Introduced to the Ottoman lands in the sixteenth and late seventeenth century, respectively, coffee and tobacco were not mentioned in either the Qur’an or the Prophetic traditions (hadith) and therefore, could not easily be classified into any legal category. Faced with the unprecedented popularity of coffee and tobacco across the Ottoman lands, Ottoman jurists produced a wide range of opinions regarding their legal permissibility. Some of these jurists – who themselves enjoyed one or both of these commodities – touted their benefits for the bodies and souls of Muslims who took pleasure in them. Others, however, insisted that not only did coffee and tobacco have neither nutritious nor medical benefits, but they even caused the pious to neglect their religious duties. Despite periodic legal challenges and occasional closures of coffee houses by some Ottoman Sultans, coffee-drinking and tobacco-smoking Muslims were willing neither to give up their enjoyment nor to stop attending the coffee houses in which they could drink coffee, smoke tobacco, exchange news, gossip, and discuss politics. By the end of the seventeenth century, the controversy over the legal properties of coffee and tobacco had faded away, only to be revived from time to time in the works of a handful of Ottoman jurists who, like al-Aqhisari himself, were latecomers to the debate. Al-Aqhisari elaborated on his opinions and rulings on the legal status of these popular commodities in his Treatise on Coffee, Tobacco, and Intoxicating Substances.

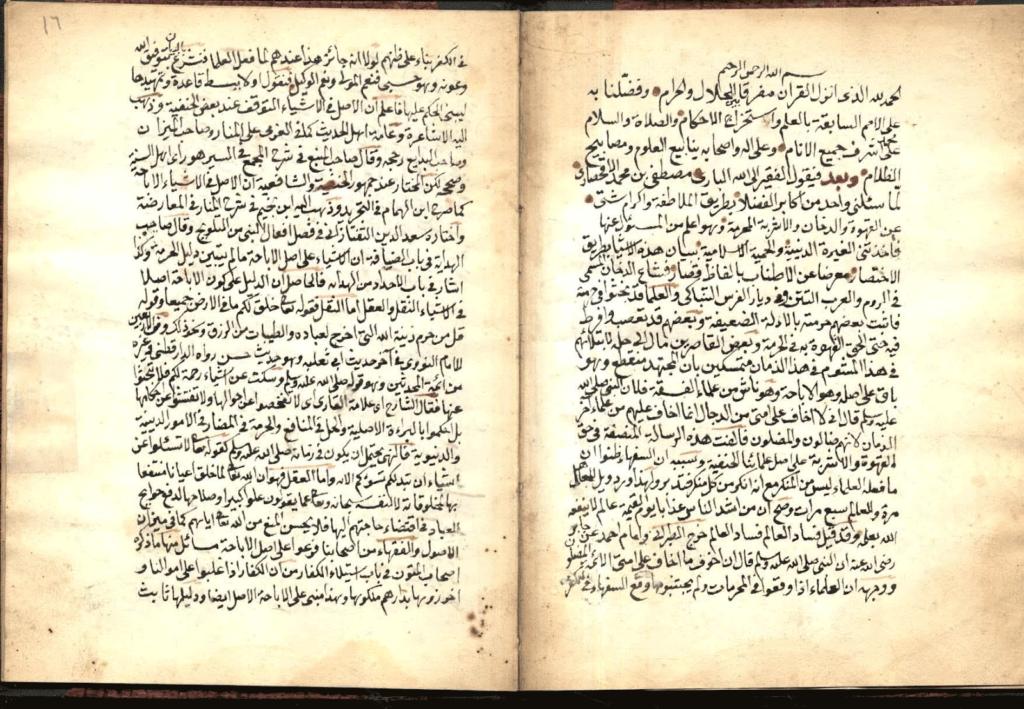

Neither a typical legal treatise nor a fatwa, al-Aqhisari’s Treatise on Coffee, Tobacco, and Intoxicating Substances occupies an ambiguous space between these two genres of legal texts. A legal treatise is usually longer, with the author’s voice clearly stated throughout the text. The text of a fatwa, on the other hand, is commonly much shorter, consisting of three lines of text: a question on a legal matter formulated in such a way as to solicit a brief “yes” or “no” answer, the mufti’s corresponding answer, and a list of legal sources he used for its formulation. Notably, a typical fatwa shows no evidence of the mufti’s authorship. By relying on selected features of each genre, al-Aqhisari wrote a treatise in the style of a lengthy fatwa, demonstrating his broad range of proficiencies. Specifically, he was simultaneously a translator of everyday speech/questions posed in vernacular language (Bosnian) into formalized legal Arabic; a reader, editor, and interpreter of pre-existing legal doctrinal texts; the author of a novel fatwa text, a commentator on the social mores and practices related to the consumption of coffee and tobacco; and lastly, an avid coffee-drinker himself. What follows is the first English translation of the excerpts of al-Aqhisari’s Treatise, which is based on a copy of an unpublished Arabic manuscript from the Ghazi Husref Bey Library in Sarajevo.

Mustafa al-Aqhisan. Risala fi hukm al-qahwa wa al-dukhan wa al-ashriba al-mahruma.

Ca 1745. MS. 761: 15a-21a. Ghazi Husref-Bey Library, Sarajevo.

The Mufti and His Text: Treatise on Coffee, Tobacco, and Intoxicating Substances

…When a man of great prominence and honour asked me to say something about coffee, tobacco, and intoxicating substances – even though he knew more than me about these issues – I became overwhelmed by pious desire and religious fervour to explain these things succinctly, avoiding excessive verbiage.

Once tobacco – called dukhan in the Ottoman and Arab territories and tanbaku in Persia – became widespread in Ottoman and Arab lands[1], Islamic scholars began to examine its legal status. Some of them used weak evidence to prove that it was prohibited. The overly zealous among them went as far as to connect coffee to tobacco, thus declaring them both prohibited. The ignorant ones who became afflicted with this calamity were inclined to declare it permissible, insisting that since no living legal scholar could make an authoritative legal decision about tobacco, it should, in principle, be considered permissible. This opinion came from corrupt scholars. The Prophet, may God grant blessings upon him, said: “I am not afraid that the danger to my community will come from the Antichrist. Rather, I am afraid that in time, my community will be led astray by misguided scholars.”[2] And so, I wrote this balanced treatise according to the doctrine of our Hanafi legal scholars,[3] because the feeble-minded think that whatever a scholar does is beyond reproach, even though these scholars may be more ignorant than anyone else. So, just think about that!

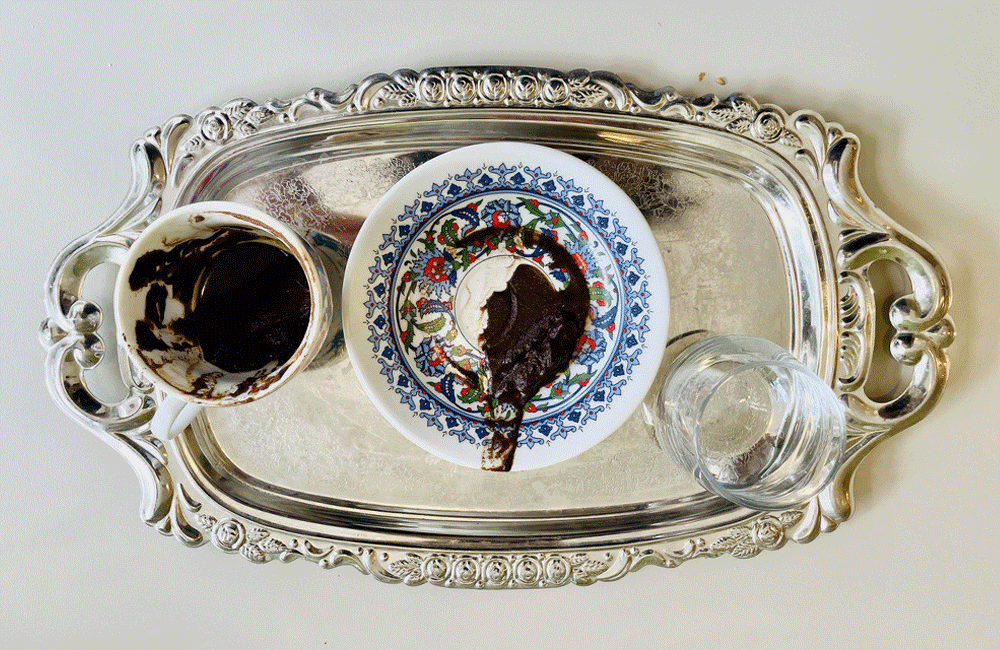

Coffee: “The Divine Drink of the Pious and Their Remedy”

One of our (Ottoman) great and prolific legal scholars, al-‘Ayni,[4] says in his Treatise on Coffee and Tobacco: “The well-known coffee is principally permissible because there is no evidence to indicate otherwise. It is not an intoxicant, or an unpleasant thing, or something that exhibits evil, or game, or a thing that entertains or anything else with reprehensible qualities. On the contrary, it is one of the pleasant things. Given that drinking coffee is not deemed to be harmful to healthy temperaments or something to be avoided, then it should be considered lawful. And why would it be prohibited by Sharia when it is not regarded as harmful to one’s healthy disposition? Moreover, coffee stimulates agility and soundness of mind and does not cause any damage. Instead, it helps to increase one’s productivity.

It is invalid to compare coffee with other forbidden things because of the absence of a common denominator [ratio legis] in the analogy between coffee and intoxicating, harmful and repulsive things.[5] As we have already presented, these qualities are not found in coffee. Many distinguished scholars – including the leading Ottoman jurists – issued their rulings that coffee is permissible. A great many of them also enjoyed drinking coffee. I have seen many learned and pious men who declare coffee lawful and drink it. I myself found that drinking coffee helps me read and stay awake at night because it fends off laziness and sleep. All who drink coffee agree with this; hence, nobody has the right to declare it reprehensible, let alone forbidden. As for the answer of the deceased mufti of Rum, Abu al-Su‘ud (Tur. Ebü’s-Suʻūd)[6] to the question regarding the legal status of coffee, which reads: “To declare these things [coffee] which are enjoyed by immoral people to be permissible would be improper,” that opinion is not correct, since there is no textual evidence whatsoever to support its validity neither in authoritative legal sources nor in practical rules derived from them.[7] Whoever reflects carefully on what we wrote here will realize the truthfulness of our words. So much about that… As for those who spoke about the prohibited status of tobacco, so claimed by the principle of analogy, the same ruling should be applied to coffee; that kind of reasoning does not satisfy anyone who has an ounce of common sense and upright character, let alone a pious scholar. To say that sinners gather to drink it does not provide grounds for its prohibition, and anyone who has the faintest idea about the art of legal rulings and their sources realizes that. Therefore, there is no weight in the words of those who equate the gathering of sinners and drinking of coffee to prove that coffee is prohibited because these two things are not interchangeable.” And so, here ends the discussion by al-‘Ayni.

Rajab Efendi,[8] May God have Mercy on Him, says: “As for coffee, it is a gentle plant and, a noble thing, and a lofty substance which God (first) revealed to a saint. He then spread it among laypeople and learned men, who held it in high esteem because of its beneficial properties and noble qualities, including preventing sleep and eliminating sadness. Coffee also stimulates worship, excites one’s desire for obedience, softens the breakfast, helps digest food, warms up one’s body and so on, which makes it as lawful as water.” Shaykh Sinan wrote: “There is no reason to consider coffee – a substance which has spread throughout our lands these days – forbidden. It is not intoxicating even when taken in copious quantities and is not harmful to one’s disposition, body, or any other characteristic, including the soundness of mind and comprehension. It does not prevent the performance of religious obligations and duties. On the contrary, it encourages them. No specific text indicates that it is forbidden, nor does it have any property to allow one to use analogy and compare it with other prohibited things. As we stated earlier, the practice of drinking coffee with excessive entertainment, like a party of the sinful, is unlawful. Tu sum up, only an ignorant zealot would think that coffee is unlawful.” And so, here ends Rajab Efendi’s argument. One learned person said:

Coffee beans make one’s sadness disappear,

For those whom knowledge endear,

Coffee, you are the song they long to hear.

You are the divine drink of the pious and their remedy,

Especially for those whose desire for wisdom is steady.

We cook it in its shell.

And when it’s ready, it has a musky smell,

And add to it the beautiful color of ink as well.

Like pure milk, it is certainly permitted,

Just think of its blackness as omitted.

God forbade it to those who are empty-headed,

Who says it is prohibited because they are pigheaded.

As for those who drink too much coffee, doctors have said: “Overindulgence of any kind is the enemy of natural disposition, especially the dry humor.”[9] Doctors have also prohibited the consumption of drinks immediately after meals. I disagree with that opinion since coffee is not a harmful cold drink but rather a warm one that facilitates the softening and digestion of food, warms up one’s body, and so on, as we explained above. When some doctors say that it is harmful to drink between two meals or eat between two drinks, they are probably talking about the consumption of cold water.[10] Drinking coffee on an empty stomach is beneficial for those with cold and damp humor, although in such a case, it is better to drink warm coffee, according to medical experts.

Ali al-Qari[11] claims that “the appointment of a person in charge of pouring and passing oxymel, milk, water and coffee prepared from coffee beans and it is passed in a single cup to a circle of people while they are gathered in an assembly is forbidden because it resembles the manner in which people drink wine.[12] Those who imitate other people become like them. Consequently, it is forbidden for men to imitate women and vice versa…” I say that is not quite the case. As the author of al-Fatawa Al-Hindiyya said, “to imitate something good for the welfare of the believers is not harmful.” If someone says that because the status of coffee is suspicious, one must give it up, I respond with the words of the author of Al-Hindiyya: “There are no such uncertainties in our time. It is incumbent upon a Muslim to beware of anything that is determined to be unlawful. Ultimately, you will not find anything that does not raise some doubt.” As al-Qari says, “When there are more things that are deemed prohibited than those that are permitted, one’s piety is reduced to the avoidance of the unlawful.”

Tobacco: “A Smoker Has No Shame”

The distinguished scholar al-‘Ayni – May God have mercy on him – stated that European tobacco leaves, known here as tobacco (Ar. tutun), are not permissible because there is unambiguous evidence regarding their prohibited status. The first evidence is an intoxication that it causes as soon as it is consumed, as many of those who indulge in it have said. The second piece of evidence is its foulness, which is the opposite of goodness. As many linguists and exegetes have agreed upon when they said: “Whatever the healthy natural dispositions find repulsive, that is prohibited according to the clear indicator in the surah al-ʻArāf: “He will make permissible for them all good things and prohibit for them only the foul.” (Q.7:157)[13]

The third piece of evidence is the indecency of smoking, which a healthy character avoids, and a sound mind disapproves. This opinion can be found in several commentaries of the verse “Surely, Allah does not enjoin indecency” (Q. 7:28). Decent and reasonable people hence disapprove when this abominable thing is used in a well-known manner, and therefore, it should be categorized among indecent things. It is customary of the Exalted God to command nobility of character and excellence of action and to forbid abomination and injustice, as indicated in the verses of the Noble Qur’an and in the Prophetic traditions. The fourth piece of evidence is the harmfulness of tobacco. Its repugnant smell, when exhaled, harms Muslims and the exalted angels. The harm of the stench coming from the mouth of the one who chewed it is even greater, particularly in the house of God. Two distinguished scholars transmit the following Prophetic hadith: “The one who eats garlic, onion or leek, should not come near the mosque.”[14] How can one who neglects these words expect God to accept their piety and answer their prayers…? The fifth piece of evidence regarding the prohibited status of tobacco is prodigality because chewing tobacco has no nutritious or medical value. On the contrary, it is harmful to the body, as many of those who tried chewing it confirmed, let alone those who tried it and then quit this habit. Prodigality is forbidden in the Qur’an, which states, “Surely the squanderers are the fellows of the Devil” (Q. 17:27) and “The squanderers will be the inmates of the fire.” (Q. 40:43),” concluded al-Ayni.

I say, this is what was on top of my mind. Tobacco distracts one from religious duties, which is quite reprehensible. The following words of God – May He be Exalted – will suffice to convince you that tobacco is reprehensible: “A person will have nothing but what they strive for.” Smoking tobacco also stimulates laziness and lassitude, especially when one does not smoke it at the usual time, for example, in the mornings. The Prophet – May God Grant Him Peace – used to pray, saying: “Oh God, save me from laziness.” Tobacco prompts the affection for the sinful and their company and the hatred and avoidance of the righteous…Another evidence of its foul properties is the increase of spit on the sides of the smoker’s mouth, staining clothes and making his beard and moustache yellow. It is said that the first question that one will be asked in the grave will concern ritual purity. Cleanliness is one of the foundations of the faith… The one who smokes tobacco rarely avoids other forbidden things. That is particularly evident in our time, among both the distinguished and the riffraff. It is said that a small sin leads to a great sin and that a great sin leads to infidelity. It is known that the smoking of European tobacco is an innovation in religion which indicates disobedience because it is said that every innovation in religion is an error, and every error leads to Hell.[15] …Another piece of evidence that smoking is not permissible is that the smoker is shameless. This is what the Prophet Muhammad said about the shameless: “The one who has no shame of people, he has no shame of God,” “When you have no shame, you do whatever you want.” Also, a smoker is a misguided person who misleads others, particularly when he is a learned man who supplies ignorant smokers with the support and evidence that smoking is permissible. Furthermore, there is fear that the smoker will, once resurrected on the Day of Judgment, find smoking implements in his hand, just as the one who drinks will find wine in his hand, and the one who plays instruments will find a lute in his hand, and so on. It is said in a hadith: “The way you lived – is the way you will die. The way you die – is the way you will be revived.”

The harmful properties of tobacco are countless and innumerable. This should suffice for anyone who has any intelligence, fair-mindedness, and willingness to listen to advice. As for the claim that smoking can be useful in curing some ailments – including hemorrhoids and the cold – that is a baseless opinion because experienced doctors do not use it in their treatments.[16] Moreover, they deny that it has any usefulness. And who, in their right mind, would burn the money that Almighty God provided for their sustenance? Since tobacco smoking has no spiritual or mundane benefits, it should be classified at best as a game, entertainment, or pastime…

The Sultan’s prohibition of smoking does not present clear legal evidence that it should be declared prohibited according to religious law, as some jurists have rushed to do. The true goal of his prohibition is to punish the insubordinate – who happened to be smokers – without citing the real reason for their punishment. In this case, the most important matter is to discipline the disobedient.[17]

Rajab Efendi emphatically states: “Purchasing tobacco, which the infidels introduced in our time, is wastefulness that leads to vices and forbidden things. It is a temptation for ordinary people and the renowned who spend a great deal of money to smoke it. It leads to squandering, which is forbidden. Besides, it has a disgusting odour that bothers the believers…Islamic legal experts say: “Whoever stinks and causes unpleasant feelings among others should be kicked out of the mosque, even if he had to be pulled by his arm or leg and not by his beard or hair.” I reason that based on this opinion, many muezzins and imams should be kicked out of mosques because they smoke disgusting tobacco and reek of its smell…